This isn’t about your parent’s definition of sharing.

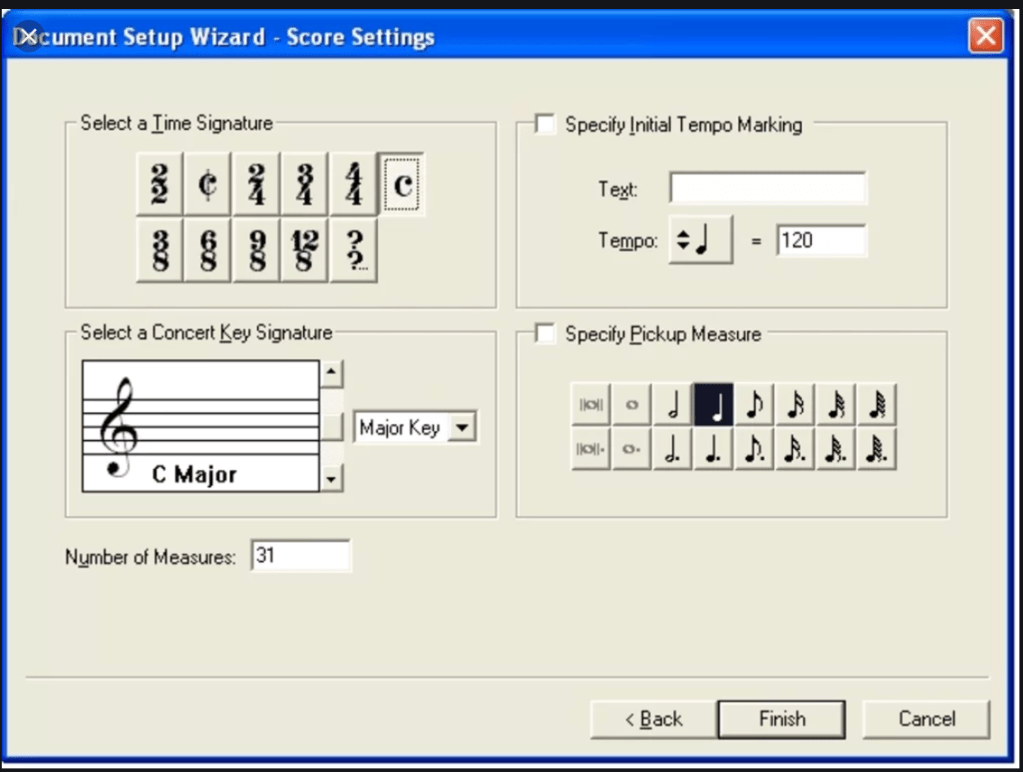

If you ever wanted to see an embodiment of Bob Dylan’s wisdom, I recommend a look at the art of composing. Truly, “the times, they are a changin’.” Obviously, this reflects an important piece of the puzzle we know as music.,..actually, creating it. Without the efforts of the masters (and a few mistresses) of the Middle Ages, Renaissance, Classical, and Romantic periods of our history, our performances will be, in a word, quiet. Twentieth Century composers began their creative periods in the same manner as their predecessors. With the arrival of notation software such as Finale and Sibelius, the creative processes (as we knew them) shifted. With these software programs and others like them, we developed the ability to do all of the regular tasks (sketching melodies, harmonizing and voicing them, etc.) formerly done with paper and pencil, but now on our desk or laptops. In addition to this sampling of tasks, we could easily convert these software files into pdf’s. If we wanted to send them off to someone needing them for perusal or rehearsal, easily accomplished…PLUS the added benefit of being able to send them mp3’s! The next natural step: taking a deep breath and sharing compositions/arrangements with everyone…anyone…welcoming in the age of Open Source.

In the spirit of transparency, I must admit that open source, and the mechanics behind it, was not on my radar until the past few weeks. I’m grateful for the opportunity to learn about it especially since this information has eased my anxieties about sharing music in an open forum…to an extent. Even as I write this week’s post, I realize that I’ve just tapped the wealth of information available about open source. In addition to this, I realize that information on open source is something that I should be sharing with my students. After all, Sir Francis Bacon was spot on when he said, “Knowledge is power.”

Here’s what I’ve learned so far: * * *Opensource.com defines open source as something that can be shared or modified simply because it is accessible to everyone. Sounds easy enough, don’t you think? Perhaps this was the case when this idea first took root. What originally dealt with software has grown to include more complex items of intellectual property and the relationships in which can be shared, such as: prototypes, formal collaborations, an equitable governance of shared knowledge or products, and so much more. * If a software program is considered to be open source, its code can be viewed or modified by anyone (I have to admit that I find this daunting). * Open source software can be used for commercial purposes. If I develop open source software, I can sell it BUT I cannot prevent anyone from buying it…even someone who would be considered “evil.”

In 1998, a community was established to support the sharing of unregistered intellectual property. Now known as the Open Source Initiative, this organized body is committed to promoting and protecting what has come to be known as the Open Source Definition (OSD)…the The 10 criteria stated in the OSD include guidelines for redistribution, clarity and ease of accessing the code (downloaded), neutrality towards the technology being utilized.

Open source as it relates to composers/arrangers/performers

This is what I want my students to understand. The software typically found in music studios, APMuTh classrooms, church music directors’ desktops, etc. is already in sync with open source (yes, this relates to Finale and Sibelius). If you’re not ready (or willing) to spend money for these systems, you can access free systems that will allow you to access the Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) that can share your music (now considered to be data) to a colleague in the next room or around the globe. As I researched for this week’s post, I was especially excited to read about Cardiod, a startup credited to a group of college students. The purpose of Cardiod is simply to provide a means for collaboration in the creative process. Union scale musicians + studio time = significant expenses. In addition to providing a richer creative canvas (I invite you to revisit an earlier post, “Location, Location, Location“), such a system will also contribute to decreasing the cost of producing new music.

The more I researched open source, the more I appreciated what this could mean on a two levels: (a) nurturing a richer creative community; (b) reducing costs for developing artists. I found myself getting stuck on two more: (a) the requirement that sharing be done regardless of whether or not the person/agency on the other side of the equation was going to use it for positive purposes or something nefarious; (b) what would this do to the professional musicians who are dependent upon studio work as a means of their livelihood. Santa Clara University (SCU)’s tie-in to Ethical Decision Making has been especially helpful as I’ve tried to move between these opposing levels. It helped me to pause long enough to recognize at least one of the Jesuit values in the discussion of open source sharing: seeking justice. When considering open source, SCU refers to 5 perspectives: utilitarian, rights, fairness, common good, and virtue. Finally! In the thick of all I found on open source, this was helping me to reconcile what the positives and challenges I was seeing. Was it enough to clear away any of the cognitive dissonance I was experiencing? No. I needed more assistance.

I think I found it. The Ethical Source Movement (ESM) recognizes the value and, perhaps more importantly, power of open source. With that, ESM states 5 criteria for software to be considered an ETHICAL SOURCE: (1) free distribution (including source code) at no cost – similar to OSD; (2) developed for public and accepting of revisions – similar to OSD; (3) governance by enforceable code of conduct – not exactly the same as OSD; (4) right of developer to prohibit its use in cases of unethical behavior and/or violation of human rights – now, we’re talking; (5) right of developer to seek reasonable compensation from those who would benefit from the software – now, we’re really talking!

The research for this week’s post has provided me with an interesting (and challenging) journey. I expect to find additional resources to assist me in my own determinations about the whether or not open source is ethical. In fact, here are just a few. As a kindergartener, I learned about “sharing.” I’m fairly certain that we all did. I also remember learning that with freedom and responsibility traveled hand-in-hand. While I learned much about the technical aspects of open source sharing, my biggest take away will probably be the need for it to be framed by ethics, especially for those of us in the musical arts.

p.s. Kudos to SCU for actually having an app for ethical decision making!

You must be logged in to post a comment.